Your organization could be functioning better.

In a recent webinar, MIT Sloan faculty Nelson Repenning, shared case studies from over thirty years of research and how they’ve informed the principles behind Dynamic Work Design. This framework (co-developed with Don Keiffer, with further refined with insights and expertise provided by Sheila Dodge) can help organizations better react to a rapidly changing world—especially when it comes to knowledge work.

Most organizations are stuck making static plans—whether it’s a budget or a marketing strategy. However, in a rapidly changing environment, those previously well-thought-out plans can’t account for all the inevitable hiccups encountered. As the organization tries to make adjustments and new rules, they inevitably create a more bloated process (and more workplace frustrations). While it’s unrealistic to get rid of static structures like budgets, there are complementary sets of structures that can be implemented to allow for a nimbler response—thus improving performance and reducing overload.

The costs of overload

When an organization (or an individual) takes on too much, it results in overloading and a decline in overall performance. All organizations are guilty of overloading to varying degrees, which is why it’s important to learn how to manage the workload to match actual capacity. Dangers of an overloaded system include:

- Inefficient task switching: If you have too many projects, you’re going to expend unnecessary mental energy each time you switch between them.

- The Capability Trap: When you have too much to do, it’s common to focus on short-term fixes versus long term investments. For example, you may be focused on closing that next sale, to the detriment of developing the sales pipeline.

- Queuing: Overloaded systems are less capable of handling variation (and any minor variation erodes performance further). Just picture a major highway during rush hour traffic—that pile up of cars is a visual representation of the workload trying to move through. If a car breaks down on that highway, that traffic becomes even more stagnant and inflexible.

Minimizing overload allows an organization to be nimbler and effectively react as the world continuously changes around them. This is just one of the five core principles of Dynamic Work Design, known as Manage Optimal Challenge, which implements the pull system.

Push vs Pull Method

Dynamic Work Design involves taking a best practice widely used in manufacturing and adapting it to knowledge work—and this means using a “pull method” versus a “push method” in prioritizing production schedules (or deliverables).

The push system, which many organizations fall prey to, has three big strikes against it:

- It’s slow: A deliverable needs to stay in its “pile” until it’s done and only then can it move on to the next step. One person could easily hold up the process.

- Individual triaging: We all have different ways of prioritizing our tasks and this introduces unpredictability, where some items will move slower through the pipeline than others depending on individualistic rankings. (Just think of your email box and how you might prioritize requests based not on actual urgency, but on who the request is coming from).

- Expediting: If you have an important deliverable that you don’t want stuck in someone’s pile, you may find a work around to ensure your request gets taken care of first and prioritized. (Maybe you’ve cornered someone in the break room to remind them about an email you sent them). However, Repenning warns this creates a vicious and inefficient cycle. Your request may move to the top, but now everyone else falls behind. Soon, others start expediting to move to the top and … well, you can see how that doesn’t help anything.

"Anything that causes you to have better conversations is key. It’s the human connection that creates the benefit."

Ultimately, a push system is clunky and inefficient. You end up with piles of work sitting at each stage of the process before they can move forward and a bottleneck—or overloading—often occurs. By contrast, with a pull system:

- You restrict the amount of work in the system. Piles aren’t allowed to accumulate at each step in the process, so you can easily see issues as they pop up. You can address where folks are behind. Or you can see where folks might be ahead and re-assign them to help stalled projects.

- You prioritize only once. Repenning uses the example of an airplane passenger list. Changes can happen to that passenger list up until the doors close. If someone wants to upgrade to first class or change their seat prior to the doors closing, it can be done. If that same VIP arrives after the door closes, it would be silly to bring the plane back to the gate and create a domino effect of chaos. Now other flights are delayed, the order on the tarmac is off, and connecting flights are impacted. (Keep that plane analogy in mind when folks are tempted to expedite).

It requires discipline, but if implemented properly, the pull system increases efficiency and flexibility.

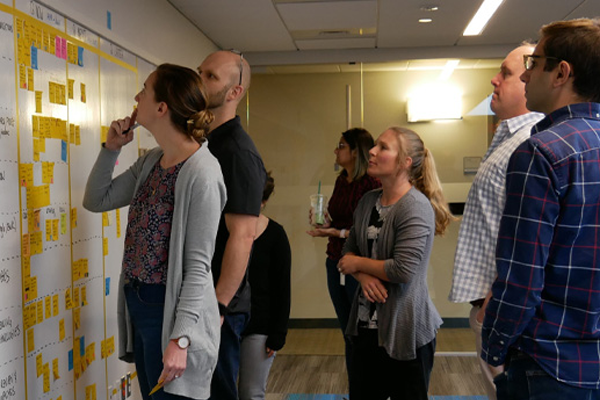

The essence of Visual Management

Visual management takes knowledge work and provides it with a visual manifestation so you can see the pull system clearly. This can be as simple as a system of post-it notes on a whiteboard. Each post-it is a deliverable and you review as a team to determine what needs to be done to move that post-it to the next step in the process. If there’s an impediment, it can be addressed in the moment instead of languishing behind the scenes. (It doesn’t have to be post-its—a software like Trello works too if you have a remote team).

Visual management:

- Gives knowledge work a physical manifestation

- Allows you to assess how much work is in the system

- Helps you populate the process

- Creates clear signals when the work stops

- Ignites problem solving

Basically, if you can see the work that’s being done, it’s easier to manage it. Repenning also cautions that the magic of visual management doesn’t lie in the post-it. The key to success is the conversations you have with your team in front of the board about why the work is moving (or not moving). If folks are skipping the meetings with the excuse that they’ll just look at the board later, you won’t make progress. “Anything that causes you to have better conversations is key. It’s the human connection that creates the benefit.”

“One weird trick!”

Repenning says that if you’re going to do one thing to manage overload, it’s important to create a “common backlog.” Everyone has their own to-do list, and it’s important to get everyone in the room and get those on a whiteboard (or excel spreadsheet, or whatever visual system works for your team). Get everyone to identify their “high priority” items, put them on a common list, then prioritize the items on that list with a hard ranking. When you have your weekly meetings, review the common backlog, and find ways to move items off the list … together. Without this common focus, everyone defaults to working on their own priorities (e.g. individual triaging) versus the joint flow of work that benefits the greater good.

How to learn more

Repenning goes more in-depth into all five principles of Dynamic Work Design during his MIT Sloan Executive Education courses (listed below). In keeping with MIT’s motto of mens et manus (mind in hand) participants are instructed to bring a small (but frustrating) problem within their organization to ultimately resolve thanks to a personalized action plan developed in class. It’s tempting to want to tackle something big, but Repenning states that by solving one small problem first, it creates momentum and a solid foundation to continue solving additional and more complex issues.

Visual Management for Competitive Advantage: MIT’s Approach to Efficient and Agile Work

Business Process Design for Strategic Management

Contributed by Elaine Santoyo Goldman