During their recent webinar, MIT Sloan faculty Scott Stern and Erin L. Scott discussed the many paths to entrepreneurial success, pulling from their research and previewing content from their new live online course, Strategy for Startups: From Idea to Impact.

Stern and Scott shared that the challenge of innovation-based entrepreneurship is not only about coming up with great ideas, but of choosing how to implement the idea in a way that creates and captures value. This is difficult because entrepreneurs often receive conflicting advice. They’re told to just go out and do it - follow the dream and everything will somehow magically fall into place. Or, they’re told to focus on very deliberate planning for success. In reality, it all comes down to choice.

Choice Matters

Entrepreneurial strategy is the sequence of choices a founder or team makes to test specific value creation and value capture hypotheses when entrepreneurial experimentation requires partial commitment. In layman’s terms? While there might be many possible paths – there is no single right answer. The key is learning enough about these alternative options to make an informed decision before deciding on the path.

So how do we learn enough about the various alternatives to figure out which strategy to choose? Stern emphasizes it’s as simple as testing two options and choosing one. The hard part is accepting that this may mean you leave behind paths that could also be viable and successful. However, you can’t (and shouldn’t) do it all.

The most critical choices you’ll need to make are:

- Who are your customers?

- How do you innovate?

- How do you organize?

- How do you compete?

You can realize an overall entrepreneurial strategy by connecting these choices together. While there may be multiple possibilities for each choice dimensions, the key is to make each choice in such a way so that they reinforce each other in terms of creating real value for customers and capturing that value in the face of competition. Very often, the fulcrum around which you can make those choices are your own passion, your own experiences, and the “unfair advantage” you bring to an opportunity.

Their new course builds on an emerging body of work at MIT and elsewhere that moves beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to startups and instead focuses on the key choices that founders face as they start and scale their business. Learn more here.

"Anyone can be an entrepreneur. The beliefs that a certain kind of person is meant to be an entrepreneur... there’s actually not much evidence for that."

Q&A

Scott and Erin covered a lot of ground during their webinar, but there are always questions from participants we’re not able to address. We’ve collected them and curated their answers below during a follow-up interview.

People have a certain vision of what it means to be an entrepreneur. Are there certain soft skills or personality types necessary for success?

Scott Stern: Anyone can be an entrepreneur. The beliefs that a certain kind of person is meant to be an entrepreneur – a lone genius, a Steve Jobs situation – there’s actually not much evidence for that.

Instead, there are traits that might make different types of people different types of entrepreneurs – and the way they might realize that entrepreneurship at different points in their career in life might be different. The key is to choose the right type of entrepreneurship and the right entrepreneurial strategy for you. For example, if you’re a person who is a bit more extroverted, you might want to choose a more execution-oriented strategy that’s more heavily focused on building a sales pipeline and really working with individual customers. On the other hand, if you are more of a systems thinker, you might go back and think how to design a platform because that’s going to play to your strengths.

Second, and here we agree with our colleague Bill Aulet -- entrepreneurship can be taught. That doesn’t mean everyone is as good as everybody else. It just means that if you’d like to be an entrepreneur you can get better at the skillset, mindset, capabilities and resources to become an entrepreneur. In fact, that is the hypothesis behind our new course -- Strategies for Startups!

Erin Scott: We also talk in our forthcoming book – Entrepreneurship: A Strategic Approach – about some of the traits of an entrepreneur. A small number of psychological “traits” – somewhat more durable elements of individual personality – do seem to predict the type of person who becomes an entrepreneur (at least in advanced economies). Most notably, entrepreneurs seem to exhibit “Openness to New Experiences” and “Conscientiousness” and also have a firmer belief in their ability to control their own fate. In other words, individuals comfortable undertaking activities with which they are unfamiliar (and may not understand in advance), and persist in navigating that uncertain terrain, are more likely to select into entrepreneurship.

Perhaps surprisingly, conditional on becoming an entrepreneur, personality traits have a much weaker relationship with the degree of success at entrepreneurship. While one can, of course, identify seemingly powerful and idiosyncratic personality traits in an icon such as Steve Jobs, countless numbers of other entrepreneurs exhibit similar traits but fail to succeed at entrepreneurship.

At least in part, that is because you do not simply choose entrepreneurship, you also choose the idea that you will pursue. We have a framework that people have found fairly valuable to help sharpen what types of ideas and opportunities to consider:

- An opportunity – You have to identify a hypothesis for value creation. What’s not being currently served in the marketplace?

- Your unfair advantage – What do you individually bring to that opportunity in terms of insight or capability or experience that might give you a leg up?

- Your passion – Why are you doing this? You answer this so you don’t lose sight of what motivates you, so you can remain persistent and resilient in the face of inevitable trials and tribulations of entrepreneurship.

Having a good answer to these three questions is a good prompt to at least consider launching a new venture. These questions allow you to understand what you are bringing to the table --- what type of opportunity, what advantages you bring, and what motivations you hold – that allow you to then focus on creating real value for customers and capturing value in the face of competition.

What is the most important misconception about entrepreneurial strategy?

ES: First, rather than simply focusing on action, we need to focus in the earliest stages of a venture, on experimentation and learning -- figuring out what to do is the first step towards creating and capturing value!

A second misconception is where to focus activity. Many entrepreneurs try and move as quickly as possible to raise financing. While financing is of course important, even more important is to clarify how to undertake strategic experiments to identify customer, technology, organization, and market choices.

And, finally, entrepreneurs often get advice about a single "playbook" for success. Our research, and just looking at different successful startups, suggests that, for a good idea and team, there are often multiple paths to value. The key is not to pretend that there is only one path, but instead to recognize that because a startup cannot pursue all paths, some potentially valuable options will be left behind in order to pursue that path that best aligns with the passion and unfair advantage that the founders bring to the venture.

How can this framework be used by existing businesses?

ES: The framework and insights in the course are relevant for both a startup and established firm that is looking to move into a new market, customer segment, or technology. While there are of course some caveats, the key is to clarify what the most important early-stage experiments need to be, how to undertake learning and experimentation without too much strategic commitment, and how to surface multiple paths to value and then focus on implementing the approach that best aligns with your organization.

It is of course useful to distinguish between the frameworks and insights relevant for a startup and an established firm. There are a lot of very powerful frameworks and research on established organizations --- the strategy field is more than 40 years old. What we have done in our work with startups and our research is develop a novel framework that starts with the specific strategic problem and challenges that face an entrepreneur. We have been really happy to see how many have found that framework useful and actionable as well for existing businesses.

How do you recommend entrepreneurs deal with a situation where the idea is so innovative that the referring companies in the field are reluctant to embrace it?

ES: The first thing that comes to my mind is: This is an opportunity! If the large firms aren’t seeing it – whether that’s because of who they’ve chosen as a customer or because of other constraints within that organization or even due to inertia – that is all an opportunity for the entrepreneur.

SS: Exactly. Choose a strategy that leverages that fact exactly as Erin said. So, what you do is identify customers, identify technology, build the team, that’s all premised on a hypothesis that the established firms are wrong. That allows you to establish your beachhead, legitimize your new approach and eventually maybe you engage in strategic cooperation. That’s essentially John Bogle and Vangaurd, Harry’s Shaving relative to Gillette, etc.

What’s the best way of trying to ensure your ‘niche’ startup is indeed niche and someone is not already doing exactly the same (or better) in the development stage?

SS: At the earliest stages, don't worry too much about someone in "stealth mode" getting too far ahead of you. While that is possible (entrepreneurship is indeed risky), most of the times that you see a cluster of start-ups pursuing the same area allows multiple startups a path to succeed (indeed, sometimes the presence of multiple players validates the new category). With that said, you should try to identify at the earliest stages the "unfair advantage" you bring -- what experience, capability, network, or insights do you have that give you advantage relative to other players? And, how can you build on and expand that unfair advantage over time?

For example, there were a wide number of crypto firms established in the early 2010s. While many have gone by the wayside due to poor operation or lack of implementation, multiple of these firms have gone on to take advantage of the growth of crypto over the last few years (and of course that space is still evolving rapidly).

What are some best practices for testing hypotheses in bringing an idea to life?

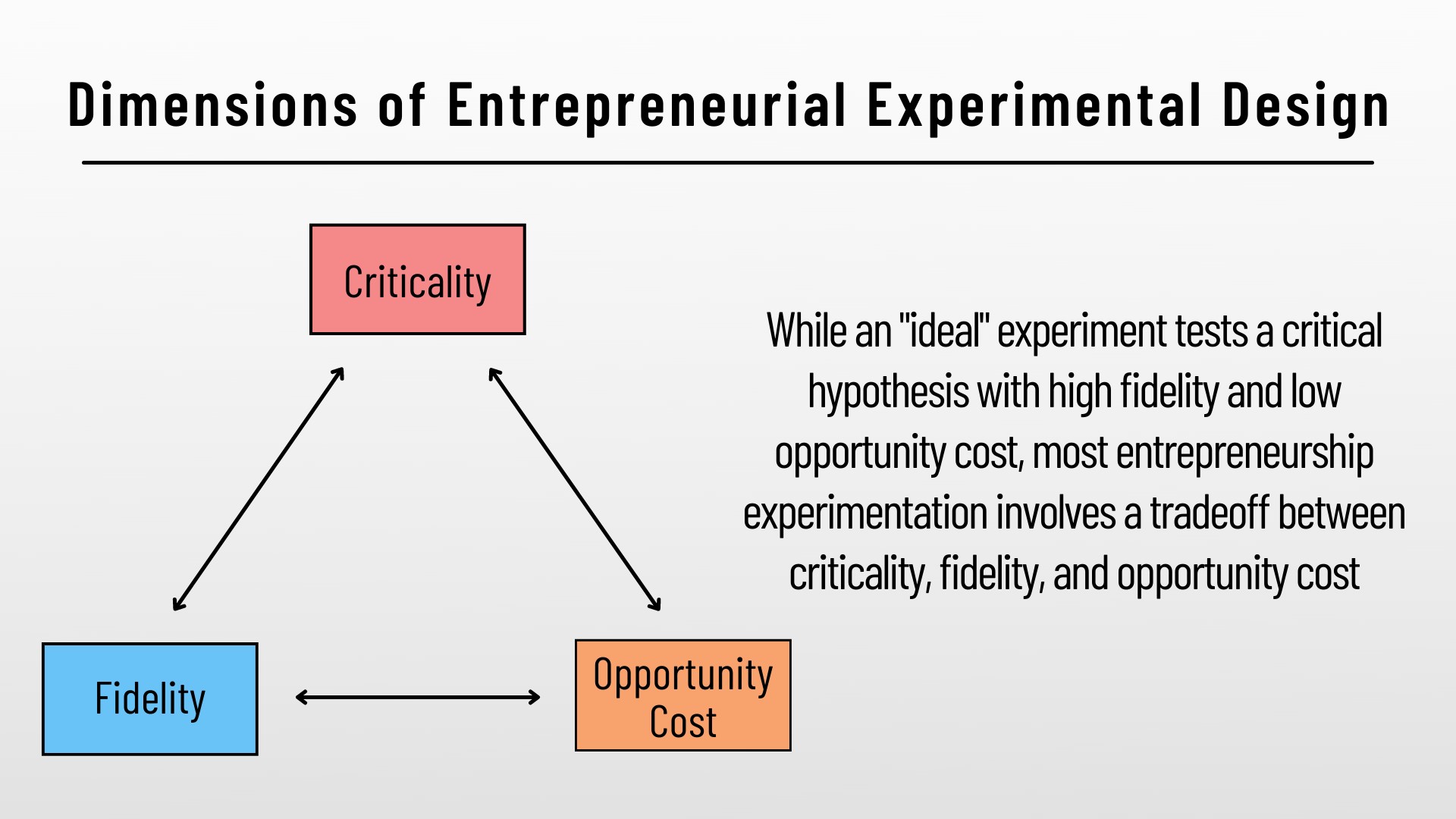

SS: The key to entrepreneurial strategy is an experimental approach to validating (or not) your most critical hypotheses in a cost-effective but informative way. It is useful to think about three critical dimensions of any experiment – the degree of criticality (is this really the most important hypothesis?), the degree of fidelity (does the experiment provide a useful test to validate that hypothesis or not?), and opportunity cost (what are the costs that come with running this experiment, including time cost, actual expenditures, and also commitments that you will make (e.g., to customers) that might constrain you going forward).

We find that, for many entrepreneurs, they are thinking about one or two dimensions, and potentially neglecting one of these three key considerations. You can formulate an experiment by asking “Am I testing my most critical hypothesis? Am I actually getting a valid test? And am I doing it without overcommitting myself to the path or overspending on the experiment?” For a startup, your own time usually has the lowest opportunity cost – and so use your time and energy to meet with people, learn about the opportunity, and gain an understanding of what is missing from the marketplace. You don’t need a perfect test or have it be zero cost – you just need to be testing your most critical hypothesis in a way that gives you a useful signal that’s not debilitating to the future optionality of the venture.

One example of this is Reed Hastings of Netflix. One of the first things that the founding team of Netflix did was send themselves a DVD in the mail. If DVDs couldn’t go through the mail – if they got broken, scratched, lost their magnetism, then the whole business would be pointless. So figure out what are some key things that have to work and go focus on testing whether you have a way to make those key elements work upfront.

ES: The key here is to reduce the uncertainty associated with the venture. By generating various types of new information, the process of testing an entrepreneurial strategy provides insight into the likelihood of success of proposed strategic alternatives and surfaces particular ways to implement those alternatives that enhances the odds of success. While the full process ultimately involves considering tests of multiple strategic alternatives (a process we go through in the course), it is useful to begin the analysis by considering the process of reducing the uncertainty associated with a particular entrepreneurial strategy proposal to implement a given entrepreneurial idea.

The most concrete consequence of stating hypotheses clearly and crisply is to help identify the underlying opportunity, the most critical risks facing a venture, and potential experiments that would allow you to clarify those critical risks at a low opportunity cost.

Guest post contributed by Elaine Santoyo Goldman