An urgent question for corporate managers and other leaders, as they rebuild their organizations and communities after the pandemic, is how to reconnect to the regional innovation ecosystems that have been so essential to corporate innovation over the past decades. This need to rebuild must be done as some question whether geography continues to be relevant in light of all that we have learned—and stand to gain—from remote work.

Our research into innovation has confirmed that robust “innovation ecosystems”—locations where innovation activity is highly concentrated and characterized by a strong social fabric of trust and exchange—have indeed remained essential. Covid-specific innovations such as vaccines resulted from these ecosystems, and there are aspects of innovation which cannot be done as remote ‘work from home’. As we have explained elsewhere, location still matters, especially as companies try to get their innovation mojo back. Before we turn to the importance on engaging strategically, a word on “innovation ecosystems”.

How we define innovation ecosystems

Our geographical definition of an innovation ecosystem is a location characterized by significant density of resources that are essential inputs into the innovation process: talent, risk capital, specialized infrastructure, and demanding customers. An innovation ecosystem is home to a wider variety of innovation stakeholders rather than the traditional “triple helix” definition of large government, university, and corporate organizations. The two essential stakeholders we add to this equation for 21st century innovation are startup entrepreneurs and the providers of risk capital who support them.

Within the most effective innovation ecosystems, these five core stakeholders come together in a dense social network to exchange resources and ideas, often through non-contractual relationships bound more by social norms and a shared culture than legal agreements. Over time, as talented people with good ideas work together with universities and seek funding and other resources from risk capital providers and corporate partners, they start to attract additional resources to the region. Success begets success, develops a regional ‘culture’ and attracts more resources and stakeholders.

"Innovation is a driver of productivity, competitive advantage, and enterprise value. But it does not happen in a vacuum. Innovation requires connections, just as entrepreneurship does, among key stakeholders."

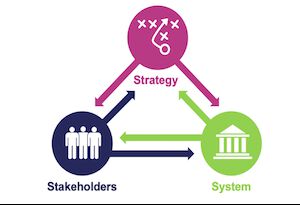

In our ecosystem approach, we emphasize three distinctive characteristics of any successful innovation ecosystem:

A robust system of innovation and entrepreneurship resources allows for strong regional innovation and entrepreneurship capacities, e.g., human capital (individuals who bring novel ideas and insights), funding at different stages of the risk capital cycle, infrastructure, and cultural incentives. These form the basis of the resources that a corporate leader may wish to access via their ecosystem engagement.

A clear set of engaged core stakeholders from five different groups—entrepreneurs, risk capital providers, universities, large corporates, and government agencies—together form the key nodes in a networked of ecosystem, alongside specialized ecosystem organizations such as accelerators and co-working communities.

The third element of this “3xS” model is the strategic focus that highlights areas of comparative advantage, enables mechanisms for effective stakeholder-wide collective action, and emphasizes the strategic necessity of focus for corporate engagement. Only by understanding the local system and its multiple stakeholders can the leader outline the right strategy.

Together these elements chart a path for improvement and acceleration at the ecosystem level by strengthening system resources, connecting stakeholders, and/or by strategically sharpening the collective focus to drive alignment and change.

The future of innovation ecosystems in a hybrid world

The shift to hybrid models of working has not fundamentally changed this basic innovation ecosystem rationale. New opportunities arise because new ecosystems are being developed and sustained at a smaller scale, as resources are drawn in from surrounding areas and distant partners.

The emerging success of places like Providence (exemplified by their Innovation and Design District) and St. Louis (named the #1 heartland city for innovation by Entrepreneur Magazine) highlight this change. This greater choice of location adds complexity to strategic engagement. Some new ecosystems will have stakeholders who do not yet appreciate the importance of their engagement with the region: they may wish to benefit from, and/or benefit, the local innovation ecosystem, but may not yet know how to do that as well as players in more established scenes.

Moreover, with the shift to hybrid working, the activities taking place within any ecosystem may be less visible, as some move online, perhaps permanently. This shift begets opportunity; new modes of interaction and connection are enabled as corporate engagement, mentoring, and even investment decisions convert to online formats.

The pandemic-induced shift to hybrid interaction means your organization can now connect to stakeholders at events from London to Lima, participate in hackathons from Sydney to San Diego, and link up with like-minded problem solvers from Boston to Bogota.

In the past, the critical human agents of the innovation economy were highly dispersed and distributed, sometimes lonely and even isolated, spread across university laboratories, working in garages and basements, often working in their local coffee shop or from home. Today, there are strong forces gathering entrepreneurs and innovators into communities and fueling programs and structured activities such as hackathons, prize challenges, accelerators, and venture studios. These new features of the innovation economy enable corporate engagement to be more effectively structured.

In Greater Boston, for example, communities have long coalesced around organizations like the Cambridge Innovation Center (CIC), which is not simply a co-working space but also a community of entrepreneurs building support, offering advice, and sharing resources.

Across the U.S., spaces like Chicago 1871 and the Brooklyn Navy Yards are creating their own momentum. Along the Mississippi Coast, universities, federal agencies, entrepreneurs, and industry partners have established the region as a leading innovation hub for ocean- and maritime-related technologies. And around the world similar communities are springing up, from Dubai’s Future Foundation to Station F in Paris, from ‘COVE’ in Halifax (Nova Scotia) and Block71 in Singapore.

Increasingly, we also observe specialized locations like Boston’s LabCentral for life sciences companies and Britain’s Manchester Landing for cyber entrepreneurs. In such spaces, innovation infrastructure supports start-up activities, but it is still the community of people that support the goals of learning and innovation.

Innovation, and strategic engagement, for competitive advantage

Innovation is a driver of productivity, competitive advantage, and enterprise value. But it does not happen in a vacuum. Innovation requires connections, just as entrepreneurship does, among key stakeholders. Even in a post-pandemic world, these connections will increasingly be taking place in innovation ecosystems and through programs such as accelerators, hackathons, prize competitions, and co-working spaces in which stakeholders and communities contribute and share talent, ideas, infrastructure, money, and connections.

It is through interactions with communities like these that corporate leaders can connect to a new community, rather than just individual teams, as well as structured, time bounded programs—such as short-term hackathons and longer-term accelerators explicitly designed to support innovators and entrepreneurs on their innovation journey from idea to impact.

In our upcoming two-day course (October 25-26), we will be exploring new insights into how best to accelerate corporate innovation, and to secure competitive advantage through more strategic engagement of innovation ecosystems and their many stakeholders.

Phil Budden is a Senior Lecturer at MIT Sloan and in MIT’s Technological Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Strategic-management (TIES) Group, where he focuses on corporate innovation, and innovation ecosystems.

Fiona Murray is the Associate Dean for Innovation and Inclusion at the MIT Sloan School of Management, the William Porter (1967) Professor of Entrepreneurship, and an associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. She is also the co-director of MIT’s Innovation Initiative.

Murray and Budden are faculty in MIT’s global Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program (MIT REAP) and lead the MIT Sloan Executive Education courses Accelerating Corporate Innovation: The Competitive Advantage of Ecosystem Engagement and Corporate Innovation: Strategies for Leveraging Ecosystems.